Blog

Groundwater Depletion Is Turning Barind into a Desert: How Satellite Science Is Exposing a Slow-Burning Crisis

The Barind Tract in northwest Bangladesh, a once-thriving agricultural zone known for its high-yield paddy fields and seasonal crops, is now facing an escalating environmental crisis. Our latest study reveals that more than 82 percent of this region is already under serious water stress. If the current trends continue, vast swathes of fertile land may face desertification within the next two decades.

This research, published in Applied Water Science (Springer), utilized a unique combination of logistic regression model integrated with remote sensing indices to map desertification susceptibility in this part of South Asia. By combining vegetation, soil, and climatic indicators, the study paints a stark picture of how environmental and human pressures are converging in one of Bangladesh’s most vulnerable regions.

The Barind Tract: A Region on the Edge

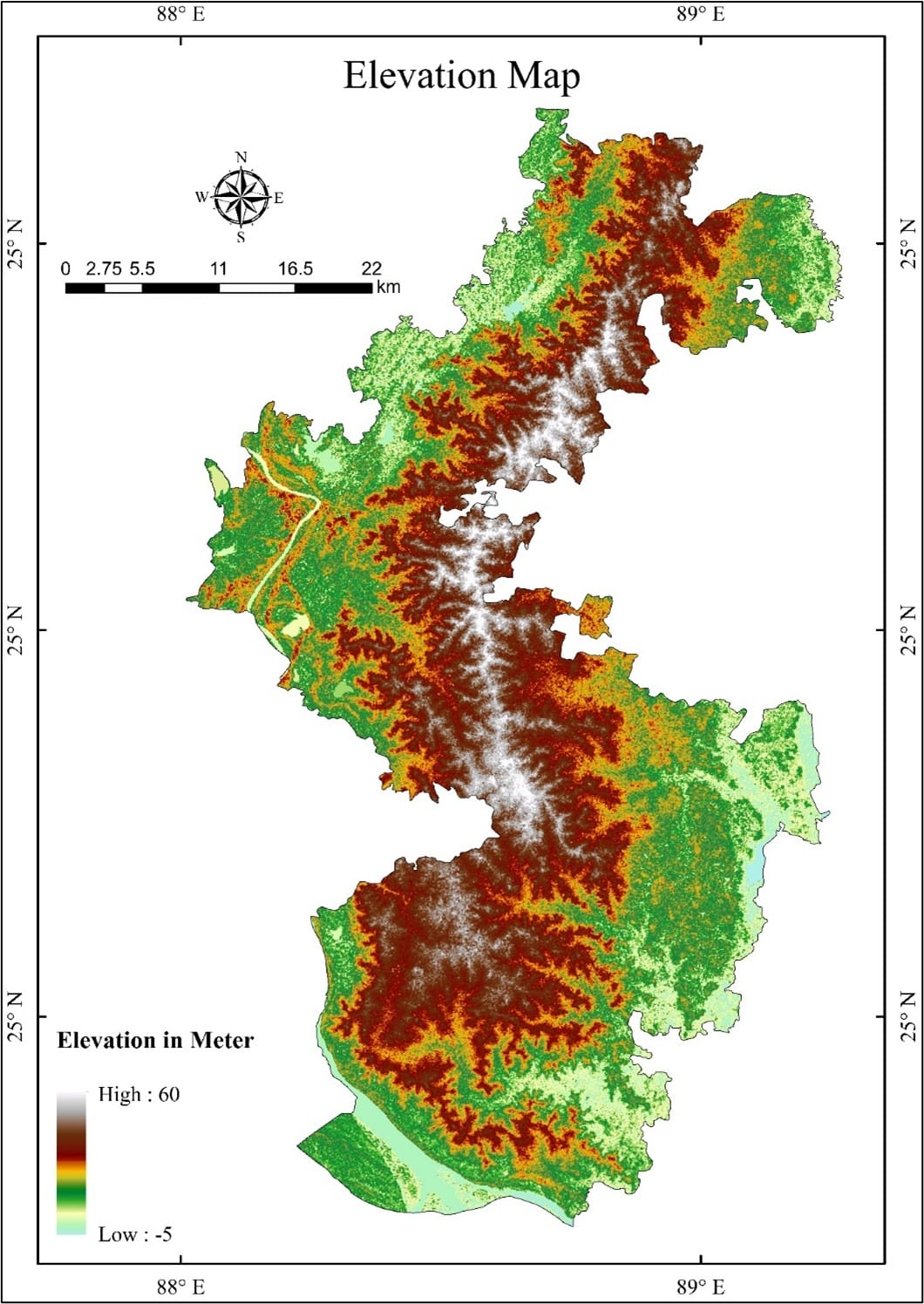

Barind tract is a geographical designation for a portion of Bangladesh’s larger Rajshahi, Nawabganj, Dinajpur, Rangpur, Jaipurhat, Gaibandha, and Bogra districts. Unlike the country’s floodplains, Barind stands at a higher elevation, receives lower rainfall (about 1,100–1,300 mm annually), and has hard red clay soils that hinder natural groundwater recharge.

The elevation highlights the natural undulation and unusual land dynamics of BT, which rise up to 60m above sea level.

Elevation Map of High Barind Tract

These results in high exposure to heat, evaporation, and challenges in groundwater recharge.

This unique geography has historically made Barind more fragile. Farmers rely almost entirely on groundwater irrigation for rice cultivation. But decades of unregulated extraction have led to alarming groundwater declines, 5 to 6 meters in some areas over just a few years.

The most vulnerable sub-districts, or upazilas, identified in the study are Porsha, Gomastapur, and Nachole, all located in the High Barind Tract. In contrast, southern zones like Godagari remain relatively stable due to their proximity to the Padma River, which provides surface water support.

Decoding Desertification from Space

To scientifically assess the desertification risk, we used satellite imagery from Landsat 9 and climate data to build three key environmental indicators:

🛰 Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI): Measures vegetation health. Low NDVI values indicate sparse or degraded vegetation cover.

🏜 Topsoil Grain Size Index (TGSI): Detects coarseness in soil particles—an early signal of land degradation.

🌡 Aridity Index (AI): Reflects the balance between rainfall and evaporation; a lower ratio indicates drier, more desert-like conditions.

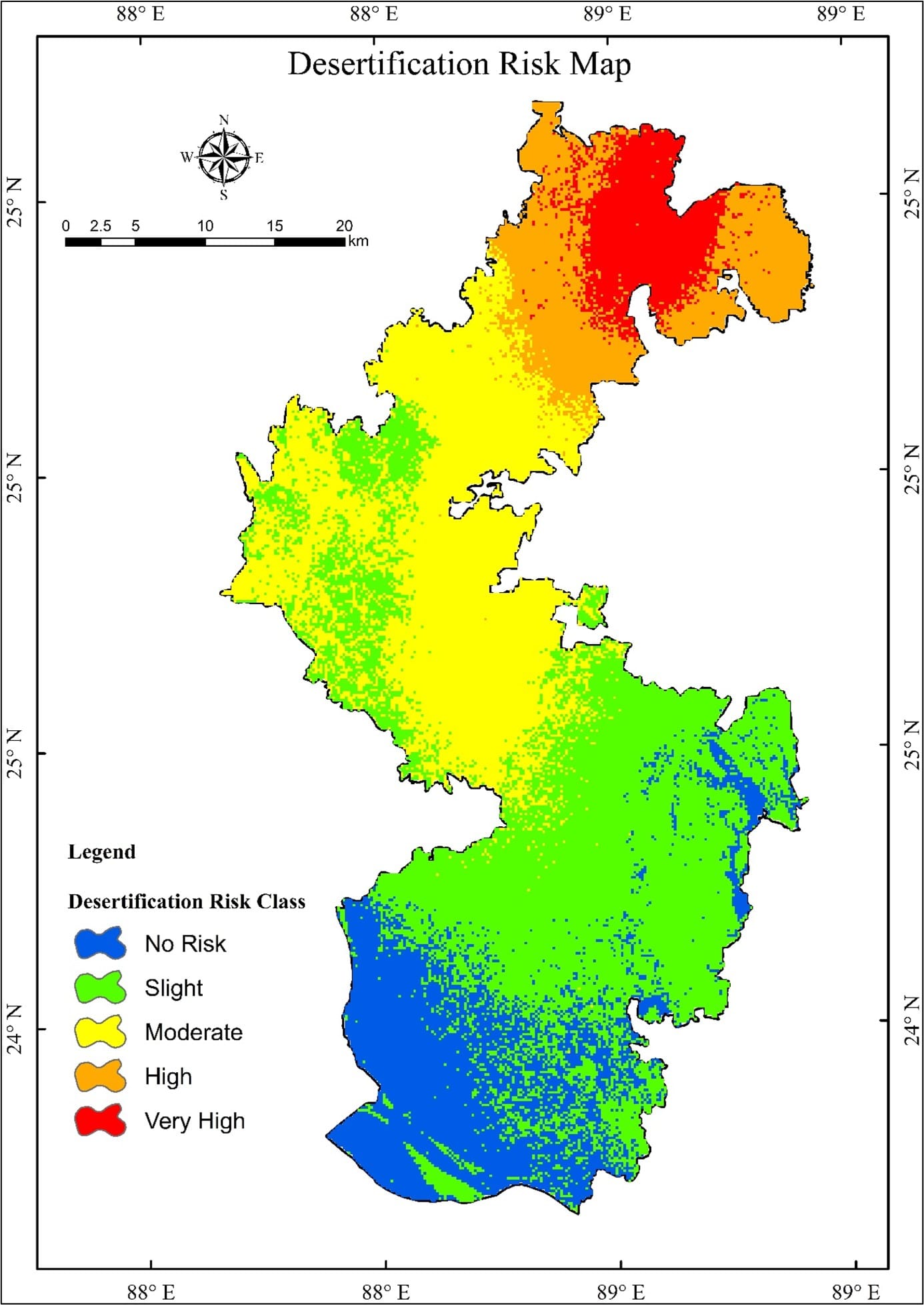

Desertification Susceptibility Map

These three indicators were standardized and combined through a logistic regression model; a statistical method commonly used in risk mapping. The model achieved a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) accuracy of 96.22%, indicating highly reliable classification of desertification risk zones. The results are sobering:

→ 6.27% (103.26 km²) of the region falls under very high risk,

→ 10.8% under high risk, and

→ 28.17% under moderate risk.

“Desertification is no longer a distant threat for Bangladesh. It’s happening silently and steadily in the Barind uplands. The science tells us that we are at a critical tipping point.”

The Dangerous Feedback Loop Beneath the Soil

The research goes beyond surface observations to understand soil–vegetation feedback mechanisms, which often drive desertification in arid and semi-arid regions. Using Rain Use Efficiency (RUE) analysis, we examined how effectively rainfall is converted into plant growth.

In areas like Porsha, RUE values were significantly low, despite receiving comparable rainfall to neighboring upazilas. This means that even when it rains, the land cannot retain enough moisture to sustain vegetation—an indicator of ecosystem stress.

Godagari, in contrast, recorded the highest RUE values, supported by surface water flow and healthier vegetative cover. This contrast illustrates a negative feedback loop:

■ Declining vegetation reduces soil moisture retention.

■ Drier soils reduce groundwater recharge.

■ Less groundwater leads to even more vegetation loss.

Human Dimensions: The Overlooked Factor

Barind’s desertification isn’t only about hydrology and climate, it’s also about human water governance. The expansion of irrigated boro rice cultivation, lack of extraction monitoring, and absence of pricing mechanisms have made groundwater depletion worse. Farmers rely on deep tube wells, often running round the clock during the dry season.

Unlike floodplain regions, Barind has almost no natural aquifer recharge during monsoon. According to Barind Multipurpose Development Authority (BMDA) data, less than 9% of rainfall contributes to groundwater recharge. With annual extraction exceeding natural replenishment, the aquifer is drying fast.

This ecological stress directly affects 5.6 million people, most of whom depend on agriculture. As crop yields fall and irrigation costs rise, farmers face increasing economic pressure—prompting rural outmigration and long-term livelihood shifts.

Pathways for Adaptation and Policy Action

The study outlines evidence-based adaptation strategies that can help avert ecological collapse in Barind:

Surface Water Utilization:

- Installing floating pontoons and rubber dams on rivers to pump surface water inland.

- Reduces dependence on groundwater and lowers irrigation costs by up to 40%.

- Water Governance Reforms:

- Introducing groundwater pricing and extraction regulations.

- Monitoring agricultural water use to prevent over-pumping.

Agricultural Transitions:

→ Promoting drought-tolerant crop varieties and regulated cropping cycles to minimize water demand.

Desertification Monitoring:

- Establishing a satellite-based early warning system to detect emerging risk zones.

- Integrating geospatial monitoring with local water management institutions.

These recommendations align with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—particularly SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation), SDG 13 (Climate Action), and SDG 15 (Life on Land).

The Broader Picture: A Warning Beyond Barind

Desertification is often associated with Africa or the Middle East. But this research shows it’s also an emerging threat in South Asia, where climate change, groundwater dependency, and land use pressures intersect.

The Barind Tract could become a test case for climate adaptation, demonstrating how geospatial science, policy, and community action can work together to prevent environmental collapse. If successful, the model could be replicated across other semi-arid regions, from India’s Deccan plateau to the drought-prone areas of Pakistan.

“The future of Barind will depend on how fast we act. We have the data, the science, and the solutions. What we need now is political will.”

📝 This article is based on:

“Groundwater sustainability assessment and desertification susceptibility mapping in semi-arid Bangladesh using integrated remote sensing and logistic regression modeling.”

Applied Water Science (Springer, 2025). DOI: 10.1007/s13201-025-02584-1

👤 Author: Ragib Mahmood Shuvo

Department of Urban and Regional Planning, RUET, Bangladesh

Email- rmshuvo2507@gmail.com